Mummies Among Us (Philatelic feature)

Wayne L. Youngblood

It’s possible there are mummies lurking in your collection – or at least parts of them.

We frequently don’t give much thought to the paper our stamps and covers are produced on, but papermaking has a long, colorful and somewhat sordid history involving various crimes, body snatching and – now – confirmed evidence of perhaps widespread use of mummy wrappings for pulp.

For many years the idea of mummy paper has been debated and was thought by many in the world of papermaking to be little more than urban legend. Mummy paper includes any number of products created using (at least in part) the linen wrappings of mummies imported from Egypt. As it turns out, from a relatively recent discovery, a number of our philatelic artifacts may contain traces of mummies.

Due to many reasons, including a rapidly growing literacy rate and the rapid expansion of the newspaper industry, the demand for paper spiked during the mid-19th century. At the time, most paper was made with a high percentage of rag content, and demand for rags far outstripped the available supply. By the mid 1850s, papermaking in America was approaching a crisis, with no significant new source of rags in sight. In Britain, it was not uncommon for criminals to dig up the recently deceased, sell the bodies for medical dissection and peddle the clothing as rags for papermaking. In the United States, however, another scenario began playing out.

Isaiah Deck, an archaeologist, geologist, explorer and physician, gave thought to mummy paper after having visited Egypt in 1847 searching for Cleopatra’s lost emerald mines. While there, he noted the huge number of mummies and parts (human and animal) that were frequently exposed in “Mummy pits” after sandstorms. By Deck’s calculations in 1855, there were enough easily accessed mummies providing linen of the “finest texture” to sate the papermaking needs of America for about 14 years (at the average consumption of 15lbs per person per year). (1.) Besides, the bones of animals (and, he presumed, humans) were already being extensively used for creating charcoal for Egyptian sugar refineries. Linens for paper, he reasoned, should be obtainable for “a trifling cost.”

Even earlier, in its Dec. 17, 1847, issue, the Cold Water Fountain, a temperance newspaper in Gardiner, Maine, ran an article regarding the potential use of mummies for paper: “The latest idea of the Pacha of Egypt for a new source of revenue is the conversion of the cloth which covers the bodies of the dead into paper, to be sold to add to the treasury,” according to the article. (2) The paper went on to describe the fine quality of the linen and its superior suitability for papermaking.

One of the earliest reports of mummies as paper pulp comes from 1858, when a visitor to the Great Falls Mill in Gardiner, Maine, complained about the smell of rags, noting “…but the most singular and the cleanest division of the whole filthy mess … were the plundered wrappings of men, bulls, crocodiles and cats, torn from the respectable defunct members of the same ... [to be mingled] with the vulgar unmentionables of the shave-pated herd of modern Egyptians…” (3) An example of a locally produced folded letter mailed from Gardiner in 1860 is shown in Figure 1. It bears an example of Scott No. 25.

Dard Hunter, in his Papermaking: The History and Technique of an Ancient Craft, documented a paper mill in Gardiner, Maine (likely Great Falls), that – in 1863 – used mummy wrappings due to a shortage of rags during the Civil War.

A History of the S.D. Warren Co., produced in 1954 to celebrate the centennial of the papermaker, discussed the shortage in a chapter detailing the transition to wood pulp. For rags, “one of the most unusual sources was Egypt, where many yards of cloth wrapped around thousands of mummies were stripped and shipped to paper-hungry countries.”3

Unfortunately oft-repeated legend that mummy linens caused multiple outbreaks of cholera in part led to the general acceptance that mummy paper was only a myth and not a reality.

However, it is well documented that in Europe mummies were being ground up for a snuff-like “medicine” and for use as a paint pigment (named “mummy”). It certainly is not only conceivable, but probable, that linens were used for papermaking in multiple U.S. locations. However, likely due to prevailing religious sensibilities regarding corpses, the use of these imports was not widely publicized.

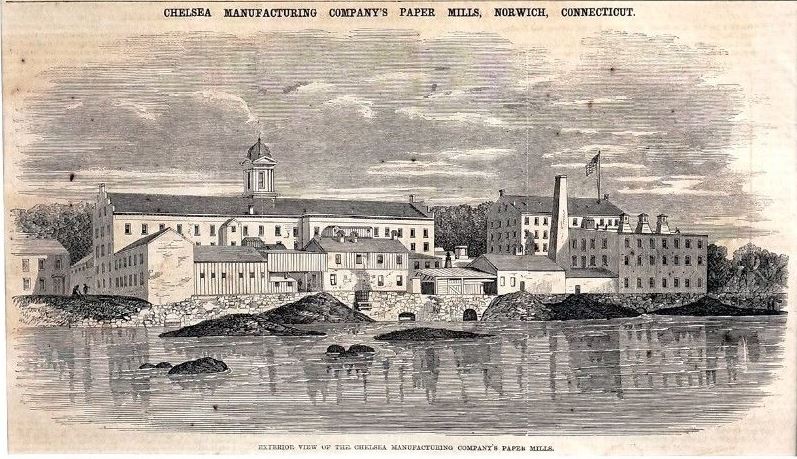

The prime piece of physical evidence is the existence of a broadside discovered by mummy researcher S.J. Wolfe in the Brown University archives, reinforced by the Figure 2 example I located several years ago – the only one known in private hands. The item was created for the Norwich, Conn., Bicentennial Celebration in 1859 and features an ad for the Chelsea Manufacturing Co. of Greeneville, Conn., at the bottom, “the largest paper manufactory in the world.”

The text, enlarged in Figure 3, reads (in part): “The material of which it is made, was brought from Egypt. It was taken from the ancient tombs where it had been used in embalming mummies…”

It’s entirely possible that a good number of U.S. envelopes manufactured during the 1850s and ’60s from multiple factories (if not stamps themselves and stamped envelopes) may very well contain traces of mummy. What’s in your collection?

Footnotes:

1. Deck, Isaiah, “On a Supply of Paper Material from the Mummy Pits of Egypt,” Transactions of the American Institute of the City of New York, for the year 1854 (Albany 1855, pp83-93).

2. A Cold Water Fountain, Gardiner, Maine, Dec. 17, 1847.

3. Northern Home Journal, Gardiner, Maine, Aug. 12, 1858.

4. A History of the S.D. Warren Co., 1854-1954, Westbrook, Maine, 1954 (page 33).