Amelia Earhart's Last Flight Cover: Not All That’s Philatelic is Stamped

By Wayne L. Youngblood

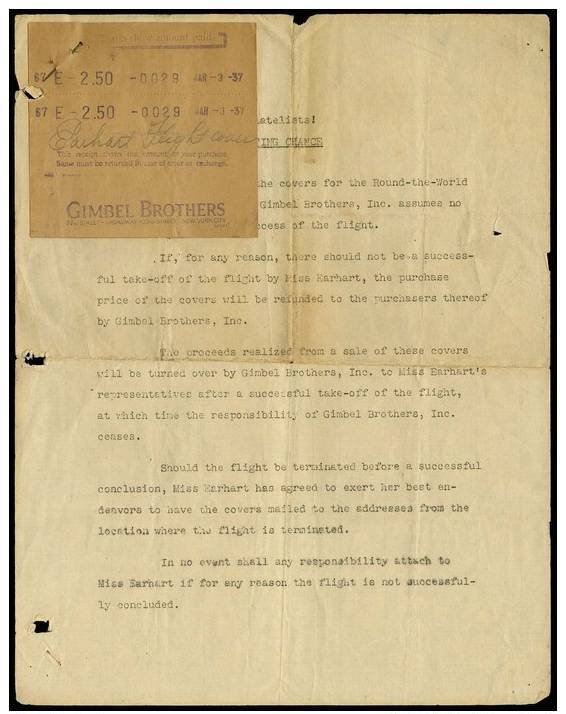

Receipt for an advance purchase of a flight cover for Amelia Earhart’s failed flight.

Sometimes, highly significant historical items from a philatelic standpoint may neither be stamped nor even have anything directly to do directly with mail delivery. They are significant purely for what they represent. One of these items turned up recently as I was breaking down a large collection. In this case, it is tied directly to aviatrix Amelia Earhart’s 1937 ill-fated attempt at an around-the-world flight. Flown covers from each of her flights are highly popular with collectors and aviation buffs alike. But when her around-the-world flight was lost July 2, 1937, so were all the covers she was carrying to mark it. Because all stamped covers were lost, the only tangible philatelic evidence of this flight includes a small number of non-serviced cacheted envelopes, including the one shown in Figure 1 from the National Postal Museum’s collection in Washington, D.C. -- until now.

Figure 1. A non-serviced cacheted envelope from the collection of the National Postal Museum. A handful of these covers previously have served as the only evidence of Earhart’s final flight.

In early 1937, to help finance Earhart's around-the-world flight, George Putnam – author, promoter and Earhart’s husband -- arranged for the Gimbel Brothers department store in New York City (home to Jacques Minkus’ philatelic empire, established in 1931) to create special red and blue cacheted covers that Earhart would carry with her in the nose compartment of her Lockheed Electra. Each of these covers would be prepaid and addressed, then delivered to collectors upon the successful completion of Earhart’s flight. A total of 10,000 covers were reportedly created, and Earhart was to add stamps and acquire postmarks along the route. Reports of the number she actually carried vary from 5,000, to 7,500 to the entire 10,000. According to information from the NPM, reports indicate that she did receive postmarks before take-off in Oakland, Calif., and again in Karachi, Pakistan. But, since the covers she carried were all lost, no one knows for sure.

Earhart began her 1937 round-the-world flight from Oakland, Calif., March 17, and set a new record for fastest east to west (Oakland to Honolulu) travel in 15 hours, 47 minutes (March 17-18, 1937). After landing, the plane was moved to Luke Field near Pearl Harbor, where it was refueled. Upon takeoff on March 20, Earhart badly damaged her aircraft, and there was serious concern about whether her journey could continue. The airplane was repaired and a second attempt departed June 1 from Miami, Fla., traveling west to east this time. The reasons for this change in direction included changes in worldwide weather and wind patterns.

Much of this second attempt went without incident and, after completing 22,000 miles, Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan landed successfully June 29 at Lae, New Guinea. On July 1, they took a short local test flight. When they left Lei July 2, 1937, for the final 7,000-mile journey (almost entirely over the Pacific Ocean), they anticipated no great difficulties in completing the flight. However, about 20 hours later (after crossing the international date line), they disappeared en route to Howland Island, losing radio contact with the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca on July 2 (July 3 in New Guinea). Although the Itasca could hear Earhart and Noonan, the aviators were unable to hear transmissions from the ship, and all contact was eventually lost. President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized a massive search, but it was abandoned July 18, slightly more than two weeks after losing contact. Putnam continued to finance his own unsuccessful search for Earhart and Noonan until October. Again, all covers being carried were lost with Earhart.

Over the years, there has been a great deal of speculation about what actually happened to Earhart and Noonan and many different scenarios have been imagined, some more fantastic than others. Several individuals have claimed to have found evidence or artifacts of Earhart’s lost flight. No verified, definitive evidence of Earhart, Noonan or her Lockheed Electra, however, has been found. Many feel that with recent searches we will soon find out definitively what happened to Earhart and Noonan. Regardless, the covers themselves are long gone.

Returning to the present, as I sifted through the previously mentioned collection, my eyes suddenly came to rest on the unassuming item shown in Figure 2. It is an original March 3, 1937, Gimbels Brothers receipt for an 'Earhart Flight Cover,' still pinned to an original disclaimer sheet regarding the sale of these covers. The receipt itself shows that the collector paid $2.50 for the cover (not the $5 often reported), and it is rouletted so that the bottom portion could be detached and exchanged for a refund, should one be allowed.

Figure 2. This recently unearthed disclaimer sheet for Earhart’s flight has a printed March 3, 1937, Gimbels Bros. receipt for $2.50 – the amount paid by a collector for one of her Around-the-World covers. The receipt serves as the only direct link to a purchased and partially serviced flight cover.

The text of the disclaimer sheet, which is chock-full of them, reads as follows:

“Philatelists! A Sporting Chance

“In the sale of the covers for the Around-the-World flight of Amelia Earhart, Gimbel Bros., Inc assumes no responsibility for the success of the flight.

“If, for any reason, there should not be a successful take-off of the flight by Miss Earhart, the purchase price of the covers will be refunded to the purchasers thereof by Gimbel Brothers, Inc.

“The proceeds realized from a sale of these covers will be turned over by Gimbel Brothers, Inc. to Miss Earhart’s representative after a successful take-off of the flight, at which time the responsibility of Gimbel Brothers, Inc. ceases.

“Should the flight be terminated before a successful conclusion, Miss Earhart has agreed to exert her best endeavors to have the covers mailed to the addresses from the location where the flight is terminated.

“In no event shall any responsibility attach to Miss Earhart if for any reason the flight is not successfully concluded.”

The disclaimer sheet itself has been folded and bears the telltale marks of having been stored in a three-ring binder, but the information is invaluable, with no fewer than three reminders of the fact that Gimbels is not responsible if the flight is not successful!

Of course, given the turn of events, neither Gimbel’s nor Earhart’s estate had to issue refunds. There was, after all, a successful takeoff.

To me, this is a fascinating -- if not somewhat chilling -- artifact of one of the most famous flights in history. Since the receipt is for a specific paid cover, it really is the closest thing we can hope for to represent a serviced flight cover.